Football and COVID-19

What happens to football players when training stops?

Early Break

Just a few months ago, there was a buzz in the air, the long-anticipated start of the season was here. Players had spent the better part of the last 3 months training through the pre-season preparing their bodies for the season ahead. But with the outbreak of COVID-19, everything has come to a screeching halt. The mandated cessation of team sporting activities has created an ‘offseason’ in the middle of regular season. It can be easy to lose focus and take a break from training. Here I write about why this is not a great idea.

Detraining effect

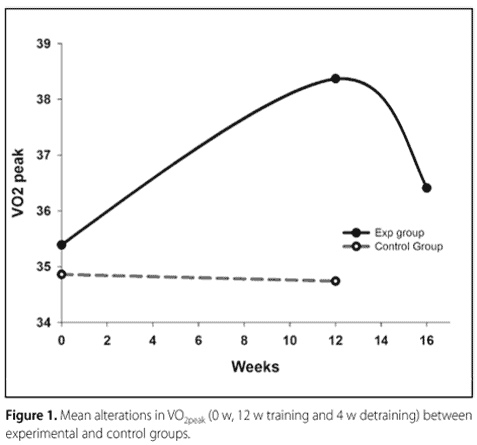

A short rest can serve as an important physical and mental respite, however longer-term effects of not training (de-training) can have a detrimental effect on both athletic performance and injury risk on return to sport. Detraining is the physiological response from the body when training is stopped; the longer the break, the faster the effect (See figure 1 below)

Just 1 week of detraining can reduce sprint speed and power performance. (1)

2 weeks of detraining in football players significantly reduces ‘Repeat Sprint Ability’ and performance in the ‘Yo-Yo Test’. (2)

5 weeks of detraining adversely affects body composition, fitness and metabolism in swimmers (3) (4)

6 weeks of detraining results in a rapid loss of endurance, speed, power, and strength performance markers; even when 3 moderate intensity runs were completed weekly. (5)

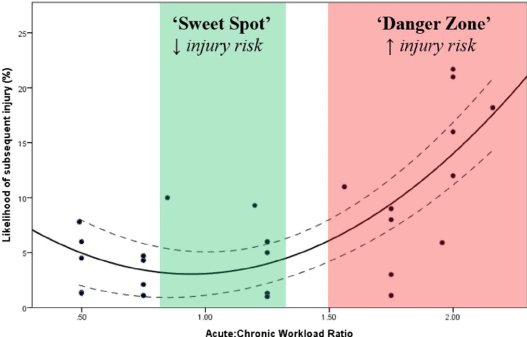

“Most injuries are caused by doing too much too quickly, after doing too little for too long”

Athletes may be planning on ‘catching up’ by training hard and doing extra sessions when the season does re-commence. But trying to catch up quickly can be detrimental too. Extensive research indicates that a period of significantly increased training/load compared to a baseline level can increase injury susceptibility (Acute Vs Chronic Workload), a rapid return to training and games is likely to put an athlete at a high risk of injuries of both strains as well as overuse injuries. (6) (7)

Take advantage of this break

Many athletes will assume that the offseason rest will be enough to settle old injuries/niggles and be ready to return for pre-season. Unfortunately, these niggles are often the result of an underlying condition which needs addressing, and the issues start to resurface just a few weeks into pre-season. By then the athlete will often feel pressure to continue pushing hard in fear of missing out on a position within the team. This break has created a unique opportunity for these athletes, a break just as these niggles are starting to resurface, and a prime opportunity to address the problems properly.

Not only can this time be used to manage the injuries, but fitness and strength can be maintained during this period simultaneously. Short term (3 weeks) rehab period was able to increase or maintain strength, and physical fitness without aggravating pain. This means players can return to the season with their injuries managed AND be fit and ready for the season to re-commence.

Is it too late to start?

Definitely not! With football likely to be more than 8 weeks away from resuming there is plenty of time to resume training and build up a base level of performance, even (especially) with some ball skills incorporated (so you don’t lose your touch).

6-8 weeks of strength and conditioning programs including weight lifting, plyometrics, sprinting, and endurance training can significantly improve athletic performance markers including agility tests, vertical jump height, sprint speed, and VO2 Max (9) (10) These effects were even more prominent when incorporated within a sport specific conditioning program. (11)

Why strength is as important as conditioning?

Strength training not only improves performance, but also reduces future injury risk. (13)

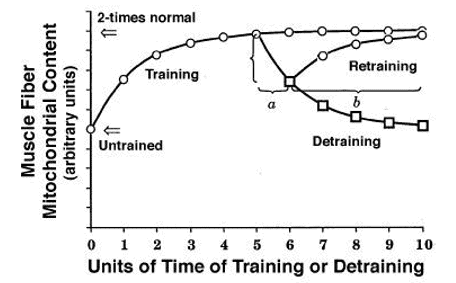

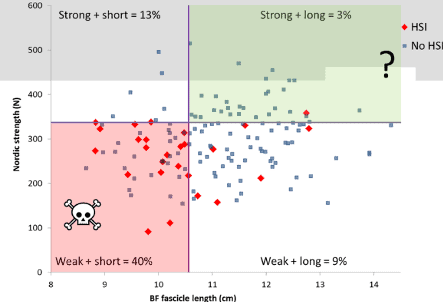

For example, research has demonstrated that the Nordic hamstring exercise, can reduce hamstring strains, (which often recur) by as much as 50% in team sport athletes when programmed appropriately. This is partly because of the eccentric nature of the exercise both strengthens and can lengthen muscle fascicle length which, the combination of stronger, and longer muscle fascicles is likely to reduce injury rates significantly (see graph below)

(14) As the graph illustrates: ‘Weak and short’ hamstrings had a 40% strain rate, compared to strong and long hamstrings which had just a 3% injury rate

Where to start?

Athletes should start by assessing their individual conditions. Any underlying injuries/niggles should be assessed, and treatment plans should be put in place.

Once this is managed, assess the current fitness and contrast this to the demands of the sport.

- What are the demands for the position?

- What are the athlete’s strengths?

- What are the weaknesses?

- When is training and games likely to re-commence?

- What resources/equipment the athlete has access to?

Once everything is considered, set realistic timeframes for the long term goals, and work backwards from there (SMART goals are never over utilised)

Need a little help? A Physiotherapist, Exercise Physiologist (Best options if you have injuries/niggles) or Strength and Conditioning Coach are all well positioned to help you get started and make the most of this time. Get after it!

References

- The effects of short-term detraining on exercise performance in soccer players – https://bit.ly/3fCt6le

- The effects of short term detraining and retraining on physical fitness in elite soccer players – https://bit.ly/3dwBe4K

- https://journals.lww.com/nscajscr/Fulltext/2012/08000/Detraining_Increases_Body_Fat_and_Weight_and.11.aspx

- Effects of short-term in-season break detraining on repeated-sprint ability and intermittent endurance according to initial performance of soccer player – https://bit.ly/2yO5wB8

- Discrepancy between Exercise Performance, Body Composition, and Sex Steroid Response after a Six-Week Detraining Period in Professional Soccer Players – https://bit.ly/35OFXMm

- The acute:chonic workload ratio in relation to injury risk in professional soccer – https://bit.ly/3dCLkBh

- The Association Between the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio and Injury and its Application in Team Sports: A Systematic Review – https://bit.ly/2STsYnH

- Acute Chronic workload – https://bit.ly/2YPmDNA

- Effects of a Unilateral Strength and Plyometric Training Program for Division I Soccer Players – https://bit.ly/2zpxxiw

- Vertical jump and agility performance improve after an 8-week conditioning program in youth female volleyball athletes – https://bit.ly/3fEqRhe

- The Effects of a 6-Week Strength Training on Critical Velocity, Anaerobic Running Distance, 30-M Sprint and Yo-Yo Intermittent Running Test Performances in Male Soccer Players – https://bit.ly/35OQMOA

- https://www.google.com/searchq=strength+detraining&tbm=isch&ved=2ahUKEwiLxPqsuunoAhUrhYKHVidAP4Q2cCegQIABAA&oq=strength+detraining&gs_lcp=CgNpbWcQAzIECAAQGDoCCAA6BAgAEEM6BQgAEIMBUJzzAVilQNgoPoDaABwAHgAgAGTA4gBix6SAQowLjEwLjYuMS4xmAEAoAEBqgELZ3dzLXdpei1pbWewAQA&sclient=img&ei=9HqWXov6A6uOmgfYuoLwDw&bih=851&biw=1766>

- Strength training as superior, dose-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis – https://bit.ly/2SVBO47

- https://www.google.com/searchq=hamstring+muscle+fascile+length+injury+&tbm=isch&ved=2ahUKEwjSnfuxunoAhUg0sFHXfDC9MQ2cCegQIABAA&oq=hamstring+muscle+fascile+length+injury+&gs_lcp=CgNpbWcQAzoCCAA6BAgAEEM6BggAEAoQGDoGCAAQCBAeOgQIABAYULUTWNJLYIlMaAFwAHgAgAHzAYgBkjGSAQYwLjMyLjWYAQCgAQGqAQtnd3Mtd2l6LWltZw&sclient=img&ei=CnyWXtLwPL6GrtoP94avmA0&bih=851&biw=1766

Comments are closed.